Last week, the news cycle swirled.

The Pope died on Easter Sunday. The world mourned and the Vatican handled procedure with quiet choreography.

Media headlines referred to Pope Francis as a “rare voice of moral clarity”—yet rare is the problem.

If the moral compass is gone, what remains?

The U.S. Supreme Court halted the expulsion of Venezuelan immigrants, forcing the nation to confront the difference between clarity and fear.

Clarity does not always come from institutions—it sometimes emerges despite them.

And the most surprising news for me, not read in the headlines, but experienced on a jog by the Alameda beach, I saw something heartbreaking. A thirty ton grey whale, washed up lifelessly on the south shore of Alameda. For hundreds of people gathered around, its enormous body turned climate change from a distant abstraction into a very real, very strange, and very local reality.

When the data rots on the beach, you can’t ignore it.

We don’t need more awareness—we need more acknowledgment.

Each event challenged people’s assumptions: admitting that even the most sacred institutions are mortal; that laws, not just leaders, can be unjust; that the cost of denial sometimes washes up at our feet.

Our Role in Clarity

We respect institutions for their endurance, but it’s their evolution that earns our trust.

While Pope Francis was widely viewed as a personal beacon of compassion and humility, the Vatican as an institution remains entangled in harm, opacity, and systemic abuse. His death, then, is not just a moment of mourning—it is a moment of reckoning. The migrant story is far from over. And more whales will starve due to environmental conditions no one seems to take responsibility for.

If clarity is a kind of perceptual freedom, maybe it starts with the bravery to look at what’s right in front of us—even (especially) when it’s uncomfortable.

Maybe it's time to ask: What is our role in perceptual freedom?

Soothers, Enablers, Agitators, and Illuminators

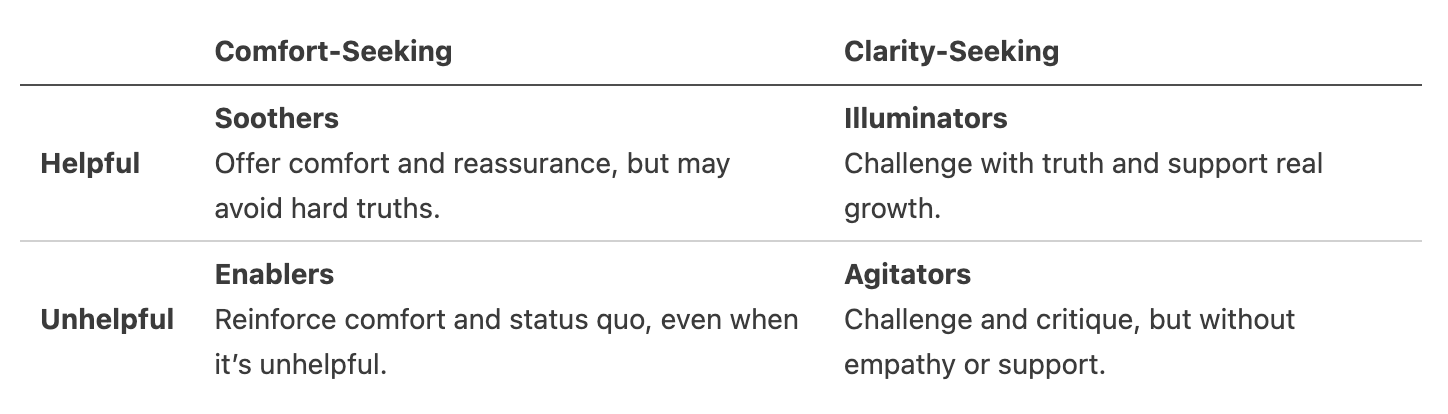

We all can find ourselves on a quadrant of clarity and helpfulness—a simple way to shape how we respond to discomfort:

The Pope, as an individual, was an Illuminator—calling for reform and compassion. The Vatican as an institution often acted as an Enabler, maintaining comfort and avoiding hard truths.

The Supreme Court’s action (halting expulsion) was a moment of illumination in a system that often defaults to comfort-seeking bureaucracy.

And the whale on the beach? Most of us, confronted with the evidence, become Soothers or Enablers—mourning, rationalizing, or looking away—while a few activists or scientists try to illuminate what’s really happening.

Where do you—and those you rely on—tend to operate? What would it look like to shift toward the “illuminator” quadrant?

A Perennial Quest

The pursuit of clarity is an ancient and noble quest. From Socrates to the present day, thinkers have recognized that clarity is the foundation upon which wisdom, inner peace, and effective action are built.1

Socratic inquiry, for example, is a powerful tool for illuminating blind spots and helping others see the world in a new light. The Buddhist and Stoic traditions, on the other hand, emphasize the importance of mindfulness, non-attachment, and distinguishing between what we can control and what we can't2. In these traditions, clarity is not about grasping harder, but about letting go of our preconceptions and biases.

Phenomenology, meanwhile, is a philosophical approach that emphasizes the importance of direct experience. By paying attention to the present moment, without judgment or distortion, we can gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us.3

But clarity is not just a theoretical concept—it's also a practical tool for living and leading. Sometimes, the highest form of kindness is helping someone see a truth they've been avoiding, because we believe in their capacity to grow and change.4

The Science of Perception and Clarity

The science of clarity reveals that it's not just a rare moment that shows up from time to time, but a skill that can be developed. Our brains are wired to predict, not perceive, reality. That's why more information can sometimes decrease clarity, especially when it confirms our existing beliefs.5

Cognitive flexibility—the ability to update our models of reality—is key to clarity. And the good news is that our brains are highly adaptable: through deliberate practice, we can rewrite them for greater clarity.6

Clarity isn't just a personal virtue—it's a powerful force for positive change. By sharing our insights and perspectives, we help others gain a deeper understanding of themselves and the world around them. That can have a profound impact.7

Cultivating Clarity: Practices and Protocols

To build a more accurate picture of the world, challenge your own thinking and seek out diverse perspectives. Two high-leverage practices for deepening clarity:

Seek Out Contrarian Feedback

Actively solicit feedback from people who are likely to disagree with you. Ask them to share their concerns and pushback on your ideas. This helps you identify blind spots and broaden your perspective.8Schedule Time for Reflection and Integration

Set aside time to reflect on your experiences and integrate what you've learned. This helps you identify patterns and connections you might have missed before.9

The Double-Edged Sword of Clarity

Clarity can be both a liberating force and a disruptive one. When we cultivate clarity, we risk exposing our own biases and flaws. But when we shrink from hard truths, we risk perpetuating patterns that keep us stuck—even at great harm to others.10

The key is to strike a balance between seeking clarity and seeking comfort. We need to be willing to challenge ourselves and others, but also to do so with empathy and understanding. Otherwise, we risk becoming either "agitators" who challenge without supporting, or "soothers" who comfort without confronting.11

The Ongoing Journey

Clarity is a continuous process of questioning, seeking, and refining our understanding. It's not a one-time achievement, but a lifelong pursuit. As our world becomes increasingly complex and dynamic, clarity is not only a valuable asset, but a critical tool for making a positive impact.12

A Direct Invitation

Where do you find yourself on the quadrant this week?

What’s one small act you could take to move toward illumination?

Who could you invite into a conversation about something uncomfortable, but important?

Remember, clarity is not just what you see—it's what you help others see, too. By cultivating clarity, you can become a catalyst for positive change in the world around you.13

If clarity is the light that reveals the world as it is, connection is the warmth that makes it worth seeing. Next week, we’ll explore how our deepest growth, resilience, and meaning are forged no in solitude, but in community.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2011). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. Guilford Press.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press.

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to Lead: Brave Work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts. Random House.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168.

Davidson, R. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity. Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 689–695.

Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2007). Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die. Random House.

Grant, A. (2013). Give and Take: Why Helping Others Drives Our Success. Viking.

Reeves, B., & Nass, C. (1996). The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places. CSLI Publications.

Aronson, E. (1999). The Social Animal. Worth Publishers.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2009). Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization. Harvard Business Press.

Langer, E. J. (1989). Mindfulness. Addison-Wesley.